On Tverskaya Street, Moscow’s most expensive shopping street, stands the impressive Central Telegraph Building, a monument of early revolutionary constructivist architecture. In the Communist era it was often the only place where foreign chess journalists could file their reports. I think I was told by the man himself that in 1956, Florencio Campomanes sent his articles on the Moscow chess Olympiad from Central Telegraph, and I bow my head, for playing in an Olympiad, as Campo did in 1956, and struggling with a Philippine newspaper deadline from Moscow, must have been quite a task. During the recent candidates’ tournament, played at Central Telegraph, Ilyumzhinov should have organized a small memorial service in honor of his predecessor.

The Dutch chess world had great hopes that if Anish Giri were to play a prominent role in the fight for first place, the Netherlands would become chess crazy again, as in the days of Max Euwe and Jan Timman. The Norwegian grandmaster and chess journalist Jon Tisdall has said that Magnus Carlsen is his pension. For me and other Dutch chess writers, Anish Giri might become our pension.

We thought that his solid style was not really suited for a tournament where first place is everything and second place little more than nothing. According to Tigran Petrosian, in a candidates’ tournament the player who doesn’t lose a game is assured of victory. And indeed, he didn’t lose in Curaçao 1962 and won the tournament. But that was after 28 rounds. For 14 rounds, solidity would not be enough.

Of course Giri was aware of the problem. In his articles he often uses phrases such as “even a boring player like me...” or similar lines. It can be seen as an ironic reaction to annoying criticism which he knew contained some truth.

In a popular daily talk show on Dutch TV before the tournament, Giri said that for physical exercise he had spent time at Papendal, a Sport Center where many prominent Dutch sportspersons have gone for training camps.

I was reminded of Jan Timman, who long ago had prepared for an important tournament with strenuous physical exercise in the healthy air of a Frisian forest. He came to the tournament bursting with energy and lost one game after another, until he repented and made up for his dangerous change of lifestyle by a night of serious drinking, after which all went well again. But what was the point of that reminiscence? I shouldn’t always try to find historical analogies.

As everybody who has followed the candidates’ tournament will know, Giri drew all of his 14 games. Internet hooligans rejoiced, creating a hashtag #girijokes on Twitter. Even decent people took part in the fun. Giri said that jokes about the subject were OK, as long as the jokes were funny. But they were not.

I must confess that I too, in a newspaper article written a few days before the start of the tournament, had called for Giri to re-style himself. But was that right? Giri pointed out that with his solid style he had been completely winning twice (true enough, I think) and about five times half-winning (which may be a bit optimistic).

But it is true, had Giri grabbed all his chances, he would have won the tournament. He said: “I don’t think there is something systematically wrong with me. It’s more a scientific miracle.” Like throwing 14 consecutive zeros at the roulette, he probably meant.

But still, what a difference with the winner, Sergey Karjakin. Giri was the only player without a loss and he was never in serious danger. Karjakin won four times, but he had five dubious positions of which he lost only once, against Anand.

One might call him lucky, as he has often been in his tournaments. But luck, for Karjakin, seems to be no accident, but a personal attribute. It stands for tenacity and self-confidence. It is said what Napoleon wanted to know above all about his generals was if they were lucky.

At the post-mortem for the official website of the tournament, Giri was always the life of the party. Eloquent, witty, charming and so talkative that his opponent was often reduced to silence. He was a joy to watch, but I sometimes wondered if he wanted to score his points in conversation, rather than at the board.

He reminded me of Peter Svidler, who also likes irony and self-deprecation. But is it accidental (to use a Marxist phrase) that Svidler once resigned against Kramnik in a drawn position and agreed a draw with Anand in a winning position? The ironist prefers to be a pleasant gentleman rather than a winner.

Again there is a big difference with Karjakin, who hardly said anything in the post-mortems, maybe because he is a heavy stutterer.

To me, Giri will be the favorite in the next candidates’ tournament if he manages to shed irony and crowd-pleasing. No more mister nice guy. The Dutch chess world heavily depends on him.

Here are a few positions to show some of the chances that Giri missed.

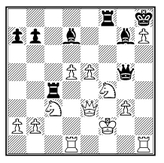

Giri-Caruana, 9th round

Giri is four pawns up and after 24.Ke1 it would have been over soon. He played 24.Rd4 which made the win much more difficult. The game was drawn after 96 moves.

Giri-Nakamura, 11th round

After 50.Re5 White would have a winning advantage, but Giri thought he could finish his opponent off quickly and played 50.Nxg7. After 50...Qxg7 51.Rg3 Rg5 he realized that he had just blundered a piece. The game was drawn after 52.Rxg5 hxg5 53.Qxd5.

Anand-Giri, 12th round

This is not really a missed win by Giri, I give the diagram because I learned something important from this game.

Giri played the passive 45...Rf8, after which he was in danger of losing. The right move would have been 45...Rc5 and then it would be White who would have to be extremely accurate to make the draw. The main line seems to be 46.Qd4 Rc7 47.Qxa7 Rxa7 48.Bxc4 Kg7 and now to my surprise White can force a tablebase draw with 49.Nxf7 Rxf7 50.Bxf7 Kxg7 51.Kg3 (only move) when this endgame King + Pawn vs King + 2 Pawns is drawn. I didn’t know that.